What does it mean to “make” sense?

Things either make sense or they do not. This tends to mean they are logical/rational/coherent vs. illogical/irrational/incoherent.

2+2=4 makes sense, 2+2=5 does not.

“Making sense” also tends to mean the difference between something that feels good vs. something that feels bad.

Furthermore, “making sense” is a phenomenon that transcends the objective and the subjective. It can exist in both realms. Maybe the flummoxing philosophy of Gilles Deleuze “makes sense,” but it doesn’t “make sense” to me. Similarly, just because I feel there is a sense to the way I clean my room doesn’t mean that it will make sense to others.

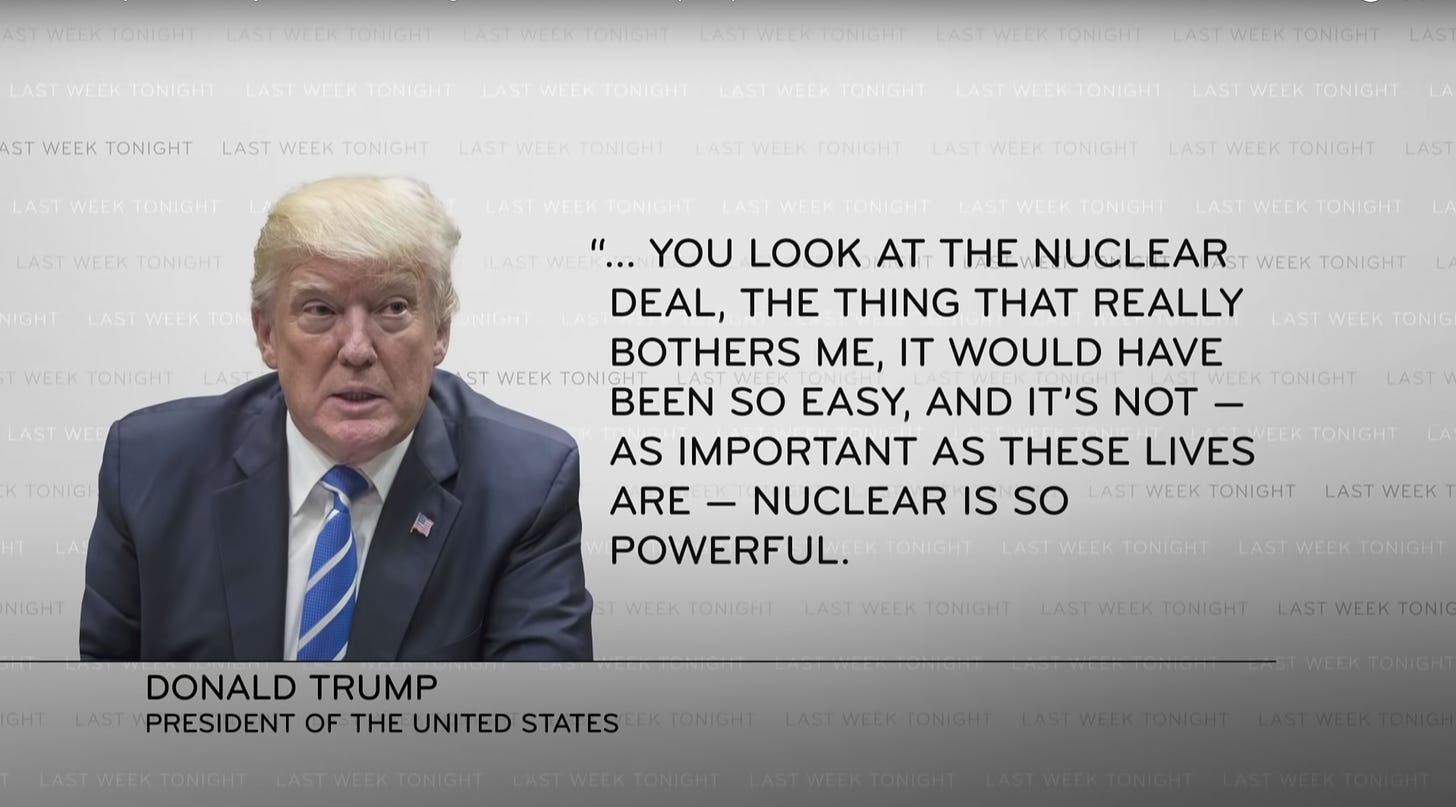

Sense is a highly dynamic phenomenon that changes with different contexts and framings. Take the much mocked rhetorical stylings of Donald Trump, whose speech seems to “make sense”, but when transcribed seems to make no sense at all.

Whatever this “sense” is, it seems very important that things be making it.

It’s strange that our phrase to describe something being rational is “makes sense.” Literally “create sensation.” That sounds like something irrational, our intuitive, subjective, emotional reaction to something regardless of its objective character.

But this mystical, irrational “sense” is exactly the force that drives our curiosity.

When things do not make sense to us, we are disturbed. We seek sense. The sense is beautiful to us.

This is the force that generates our constant intrinsic creativity, but is also a weakness that can be highjacked.

C. Thi Nguyen has written extensively about the seductive quality of clarity, which is simultaneously a useful tool and an exploitable vulnerability. On one hand, our desire for “sense” is exactly what propels us towards the truth, but our discomfort with confusion sometimes causes us to cling to sense before we’ve reached the best interpretation of reality.

“We often use our sense of confusion as a signal that we need to keep investigating, and our sense of clarity as a signal that we’ve thought enough. Our sense of clarity is a signal that we can terminate an investigation.”

Every logical fallacy, conspiracy theory and oversimplification are manifestations of seductive clarity, sense-making that steers us away from the most valuable Truths.

So suffice to say that although the Truth makes sense, something doesn’t have to be True or comprehensive to make sense. The ability to generate sense is not dependent on its traditional rationality or mathematical objective irrefutability.

This starts to elucidate the phenomenon of sense as something more complicated than perfect logical reason. This isn’t to diminish the value and reality of the Truth, but to point at the dynamic, emotional center of it. There is a sense of beauty and harmony that draws our attention towards Truth, and is the ultimate marker of Truth. After all, we wouldn’t find 2+2=4 to be so logical if it didn’t feel so good, and make so much sense.

William James describes remembrance of personal experience as “direct feeling; its object is suffused with a warmth and intimacy to which no object of mere conception ever attains.” The quality of intimacy tied with our memories is not a result of perfect reasoning, but this mystic, unscientific “direct feeling”.

This is the sense that comes from True knowledge, or at least the perception of true knowledge.

But if “sense” is generated by both actual Truth and the false sensation of truth, is sense just a meaningless accident? Not exactly.

Oftentimes what we call “Truth” is really a dynamic set of heuristics, or useful tools we use to navigate the flow of reality successfully. When faced with reality, we develop experimental hypotheses of what might be true (or useful to believe), and then we try them out to see if they lead to positive results in our lives. The experimental theories that work the best are then granted the accolade of “True” until they are proven incomplete or unhelpful, at which point we reconstruct them.

What makes truths like 2+2=4 so longstanding is how incredibly successful they are when applied to any situation. The immediate warmth and intimacy we experience looking at the logic of such an equation is maintained no matter what context it is thrust into, and this consistency allows us to usefully plan, predict and interpret our lives.

Mathematician Henri Poincare wrote extensively on the philosophy of science, particularly chronicling the mystical intuition that inevitably guides it. As philosopher Robert Pirsig would later summarize:

Mathematics, he said, isn’t merely a question of applying rules, any more than science. It doesn’t merely make the most combinations possible according to certain fixed laws… The true work of the inventor consists in choosing among these combinations so as to eliminate the useless ones, or rather, to avoid the trouble of making them, and the rules that must guide the choice are extremely fine and delicate. It’s almost impossible to state them precisely; they must be felt rather than formulated.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig, 1974

The spark that creates such theories is always the intuitive sense of Quality itself.

The thing you feel is the sense that is made by particular combinations of facts. An intuitive harmonious beauty simply radiates from these things.

So sense generation is a completely valid thing to keep your eye out for. In fact, it’s kind of all there is to look for. But just because something makes sense for a moment, or in one context, doesn’t mean it will be True in all circumstances for all of time.

Sense has a relationship to Truth/usefulness/beauty. It’s part of our experimental groping for it, the emotional reverberations that tell us we are close to something that might be useful. Then the tests of transferability, verifiability, and utility inform us whether the sense generating thing is valuable enough to be granted the honorific of “True.”

…enough. For now, at least.

When all these little nuances are parsed, it really highlights the subtle beauty of our linguistic heuristic “make sense.”

When a thing we experience makes sense, it literally generates an intuitive warm feeling of meaning that we are drawn to, and we name it as doing so.

We can suspect that something makes sense by the testimony of others, but it doesn’t make sense for us until we know it as intimately as warmly as one of our own memories. Alternatively, things that make sense for us personally might not make sense to others, some things make sense emotionally that don’t quite make sense on paper, and some things make sense for just a second before they collapse into unintelligibility once more.

The takeaway here is no revelation: the naming of what patterns create Sense in us and which don’t is an astute distinction that is incredibly accurate to our emotional and intellectual experience as individuals and in relationship to the world and others.

Many phrases we use daily are wonderfully vivid, including something as small as whether or not something makes sense to you right now.

We’re smarter than we think we are.